Bio courtesy of legendsofamerica.com

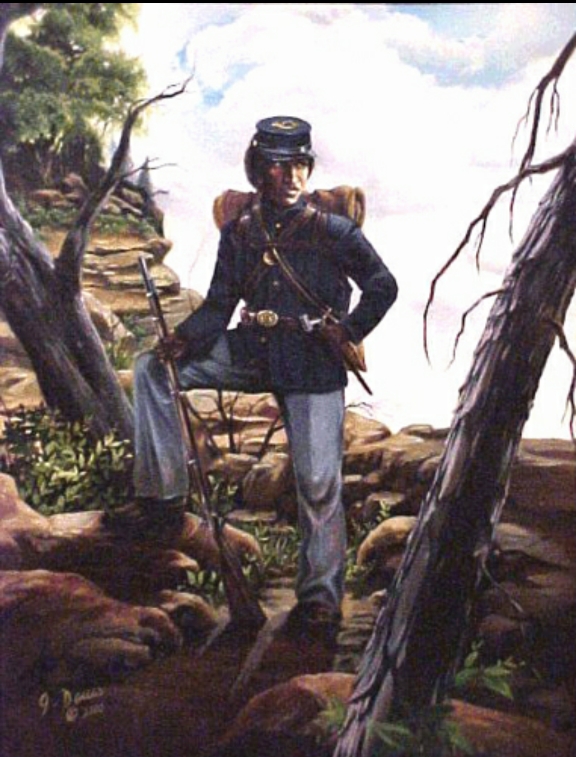

When Congress passed an act authorizing the establishment of the first all Black units of the military, later to become known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” Cathay Williams, a former slave, joined the Army. At that time, women were not allowed to serve as soldiers so Williams posed as a man, calling herself William Cathay.

Williams was born into slavery in Independence, Missouri in 1842. She worked as a house slave for William Johnson, a wealthy planter in Jefferson City, Missouri until his death. Shortly after the Civil War broke out she was freed by Union soldiers and soon went to work for the Federal Army as a paid servant. While working in this capacity, she served Colonel Thomas Hart Benton while he was in Little Rock, Arkansas as well as General Philip Sheridan and his staff, experiencing military life first hand. Sheridan brought her with him to Washington to serve as a cook and laundress.

While traveling with them, she witnessed the Shenandoah Valley raids in Virginia, and afterwards continued to travel with them to Iowa, St. Louis, New Orleans, Savannah, and Macon.

When the war was over, Williams wanted to maintain her financial independence and in November 1866, she enlisted as William Cathay in the 38th U.S. Infantry, Company A in St. Louis, Missouri. At that time, only a cursory medical examination was required and she was quickly found to be fit for duty. There were only two people that knew her true identify – a cousin and a friend, who faithfully kept her secret. She informed her recruiting officer that she was a 22-year-old cook. He described her as 5′ 9″, with black eyes, black hair and black complexion.

On February 13, 1867, Williams was sent to Jefferson Barracks, Missouri and a few months later, in April, the troops marched to Fort Riley, Kansas. By June, they were on the march again, this time to Fort Harker, Kansas, and the next month, on to Fort Union, New Mexico, more than 500 miles away. On September 7, the regiment moved on to Fort Cummings, New Mexico, arriving on October 1st. They were stationed there for eight months, protecting miners and traveling immigrants from Apache attack. While she was there, a brief mutiny broke out in December, 1867 when a camp follower was expelled for stealing money. Several men were brought up on charges or jailed, but Williams was not among them.

It did however, take a toll on her and seemingly her health was suffering, as she was recorded as being in four different hospitals on five separate occasions. Amazingly, during these various hospitalizations, it was never discovered that she was female.

Fort Bayard, New MexicoOn June 6, 1868 the company marched once again, this time to Fort Bayard, New Mexico. By this time Williams longed to be quit of the army and, on July 13, she was admitted into Fort Bayard hospital, this time diagnosed with neuralgia – a catch-all term for any acute, intermittent pain caused by a nerve.

It was during this hospitalization that it was finally discovered that she was a woman. On October 14, 1868, William Cathey and was discharged at Fort Bayard with a certificate of disability, which included statements from the captain of her company and the post’s assistant surgeon. The captain stated that Williams had been under his command since May 20, 1867 “… and has been since feeble both physically and mentally, and much of the time quite unfit for duty. The origin of his infirmities is unknown to me.” The surgeon stated that Cathey was of “…a feeble habit. He is continually on sick report without benefit. He is unable to do military duty…. This condition dates prior to enlistment.”

Over her two year stint Williams participated in regular garrison duties but there is no record that she ever saw direct combat while she was enlisted. Though seemingly not well regarded by her commanding officer, she was honorably discharged with the legacy of being the first and only female Buffalo Soldier to serve.

Afterwards, she worked as a cook for a colonel at Fort Union, New Mexico in 1869 and 1870. She then moved on to Pueblo, Colorado, where she worked as a laundress before permanently settling in Trinidad, Colorado in 1872. There, she made her living as a laundress and part-time nurse. Some years later, her failing health arose again when she was hospitalized in early 1890, for nearly a year and a half. By the time she left the hospital, she was completely without funds and in June, 1891 filed for a pension from the U.S. Army. Her application claimed that she was suffering deafness, rheumatism and neuralgia, all of which she had contracted while in the army.

However, after various doctor’s exams and investigation, the Pension Bureau rejected her claim on medical grounds, stating that no disability existed. Further, they found that her discharge certificate indicated her feeble condition pre-dated enlistment and was not due to service. Lastly, and most obviously, her service in the Army was not legal, and any type of pension, disability or otherwise, was denied.

What happened to Cathay Williams afterwards is unknown, but it appears that she may have died sometime between 1892 and 1900 as her name no longer appeared on Census rolls from 1900.